Article By: Aisling Carroll

California’s 21 public health care systems have been serving on the front lines of the pandemic from the very beginning, caring for anyone who walks through their doors and going out into the community to ensure equitable access to care. In addition to being local anchors for health care, they have partnered with community-based organizations to address food insecurity and sent teams into the streets to care for persons who are homeless.

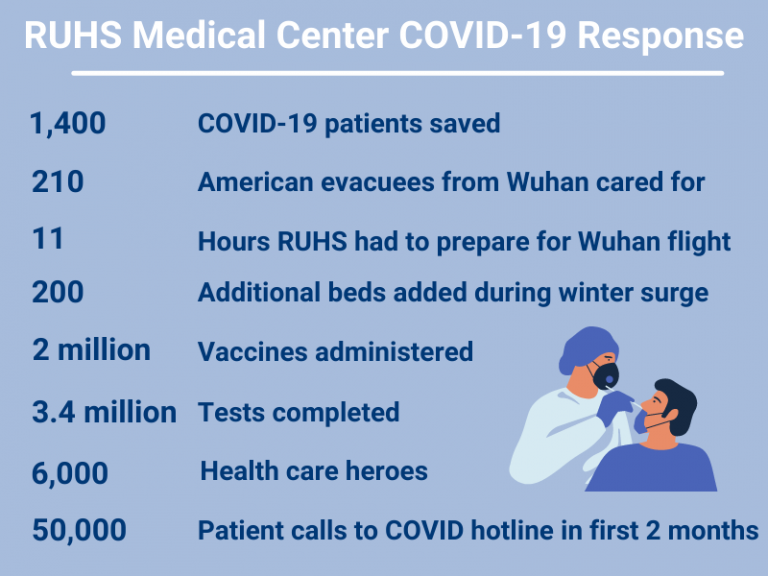

As these systems continue to battle Covid-19, Riverside University Health System Medical Center recently shared their experiences. This story is just one example of how public health care systems have been swiftly and effectively meeting the moment, from expanding access to testing and increasing surge capacity to distributing vaccines for some of the state’s most at-risk patients.

A deep culture of preparedness

As the wheels of a chartered plane from Wuhan touched down on the tarmac of March Air Reserve Base on January 29, 2020, Jaime Hurtado, 55, sat on his couch a few miles away, stunned by what he saw on his TV screen. This plane full of nearly 200 Americans evacuated from the global epicenter of Covid-19 was landing in his hometown of Riverside, making international news.

“We didn’t know anything about the virus then,” said Hurtado. “And I thought, ‘What if it gets out?’ This is a low socioeconomic area; many people don’t have health care.” A longtime county employee who was active in his community, Hurtado worried for those who were just getting by. He never thought of himself.

The evening before the plane landed, Jonelle Morris, chief operating officer of Riverside University Health System Medical Center (RUHS Medical Center) and an RN, received a message that the flight was making a last-minute diversion to Riverside. RUHS Medical Center is one of the largest hospitals in Southern California with 439 beds, 60+ clinics and a mission to care for everyone who needs it, regardless of an ability to pay or insurance status.

Morris immediately joined calls with military leaders who briefed her and RUHS Medical Center colleagues about evacuees needing medical care upon arrival. That care would be required on the base for as long as the federal quarantine, the first imposed in 50 years, lasted in order to protect the general population.

RUHS Medical Center had 11 hours to prepare a full-scale medical response, which included supporting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with Covid-19 screening of evacuees.

Morris swiftly sprung into action. She woke doctors and nurses at home to recruit their help. She mobilized RUHS Medical Center’s resources, unfurled quarantine protocols and coordinated with county emergency officials throughout the night. RUHS Medical Center’s disaster medical team already had close relationships with emergency personnel, speaking regularly.

“We knew we could meet the need because of how tight-knit this RUHS Medical Center team is,” said Morris.

Morris and her strongly aligned team also had a deep culture of preparedness at their backs. For more than 125 years, the hospital has led emergency responses to some of the country’s most perilous situations, from the 1918 Spanish flu and polio to earthquakes and the 2015 San Bernardino mass shooting.

“We didn’t know anything about the virus then. And I thought, ‘What if it gets out?’ This is a low socioeconomic area; many people don’t have health care.”

– Jaime Hurtado

Caring for potentially Covid-positive evacuees

Before dawn broke, RUHS Medical Center drove its core capabilities to the March Air Reserve Base in the form of a massive mobile health clinic. It contained three separate exam rooms and several clinicians, from emergency medicine doctors to psychiatrists.

Given evacuees were under a unique stress, they had a high demand for a variety of non-Covid related care during their quarantine. From the 24/7 RUHS Medical Center team, they received everything from electrocardiogram tests and prescriptions to tools to cope with anxiety. Soccer balls were distributed to occupy the younger evacuees.

Fourteen days later, with no one testing positive for Covid-19, evacuees tossed their masks in the air. They were jubilant to end their quarantine. Looking at the wider, unknown picture, Morris and others at RUHS Medical Center were less enthusiastic. Although there were no reported cases in Riverside County in early February 2020, they eyed potential catastrophe ahead.

Fourteen days later, with no one testing positive for Covid-19, evacuees tossed their masks in the air. They were jubilant to end their quarantine. Looking at the wider, unknown picture, Morris and others at RUHS Medical Center were less enthusiastic. Although there were no reported cases in Riverside County in early February 2020, they eyed potential catastrophe ahead.

“Nonstop from the time that plane landed”

“This is only one flight,” Morris thought. Airports across the country still teemed with travelers.

Eager to get a jump start on what a sustained response to the coronavirus might look like, Morris and her leadership team worked with the hospital’s infectious diseases doctors, scrutinized supplies and stocked up on more masks, gowns, glasses and shields.

They also played out possible surge scenarios, drawing up plans for where they would care for a large influx of Covid-19 patients and who would do the caring.

For example, if the hospital was overrun, its leaders would convert non-ICU areas, such as post-surgery recovery rooms, into ICU beds. They would redeploy and train doctors and nurses from RUHS Medical Center clinics in the area to care for these patients. They would incorporate medical residents into these new clinical teams. They would place roving behavioral health professionals throughout the hospital to emotionally support patients, their families and staff.

As expected, Covid-19 quickly took root and spread in Riverside.

“It was nonstop from the time that plane landed,” said Morris. Clinicians and staff, however, continued to meet patients’ physical and psychological needs. “We never stopped seeing patients.”

Whether through a car window or a cell phone or computer screen (i.e., telehealth), patients received everything from checkups to crisis therapy. And for those suffering heart attacks, strokes and injuries, the ER was in full swing with separate pathways established to protect non-Covid-19 patients. Elective surgeries and certain procedures, however, were paused when coronavirus cases spiked.

“It was nonstop from the time that plane landed.” Clinicians and staff, however, continued to meet patients’ physical and psychological needs. “We never stopped seeing patients.”

– Jonelle Morris

Bringing labs in-house and buying more phones

To slow transmission rates, Morris developed and launched an extensive testing program in March 2020. She set up permanent testing sites and pop-ups in communities impacted the most. Donning her scrubs at times, Morris also helped swab health care workers.

As testing increased, there were delays as outside labs struggled to keep up with the high volumes. To ensure patients could know their test results as rapidly as possible and take steps to protect others, Morris brought testing in-house with a mobile lab.

And to answer the blitz of questions patients had about testing and symptoms, she marshaled staff and bought dozens of phones to establish new call centers. As soon as they mastered the operation, Morris wrote up a playbook for future reference.

Riverside’s surges shatter infection records

The 2020 Memorial Day weekend and a pandemic-weary public unleashed Riverside’s first surge. By late June, Riverside County had the second-highest number of coronavirus cases in the state.

As the positivity rate shot up, throngs of patients swarmed in and hallways crowded, RUHS Medical Center started executing its previously drafted surge plans. But this was only the first crush of Covid-19 patients; the second was far worse.

On the heels of another holiday (this time, Thanksgiving), the hospital was pushed to the brink in December 2020 and January 2021. With overwhelming numbers of very ill patients, many of them Latinx essential workers from the area’s manufacturing facilities and distribution centers, hospitalizations shot up by 40 percent compared to a regular year. Available ICU capacity was zero and there were fewer nurses per patient due to a severe state shortage.

The hospital was “pulling out all the stops,” said Jennifer Cruikshank, chief executive officer of RUHS Medical Center, as reported in the Press-Enterprise. In a constant state of on-the-spot improvisation, the hospital placed beds “in places you would never imagine,” said Morris.

A former storage room was converted to house 10 ICU patients. Moms-to-be made way for Covid-19 patients whose ravaged lungs required the oxygen dispensers on the walls of the delivery units. The laboring mothers were moved to RUHS Medical Center’s new, three-story Medical and Surgical Center, which had fortuitously opened in late March 2020 with modern oxygen-piping infrastructure.

But even with exhausted and mentally taxed staff working nonstop, the virus’ pummeling was unrelenting. RUHS Medical Center added more than 120 beds to try and accommodate the flood of patients, which was stretching the hospital beyond its licensed capacity.

Some clinicians were also stretched to their limits. Serving as last line health care workers – over and over again – RUHS Medical Center’s doctors and nurses needed to process from the anguish of losing patients. To help, RUHS Medical Center’s Behavioral Health Team set up Operation Uplift.

Drawing on the strong camaraderie among RUHS Medical Center clinicians, the program placed peer support specialists in the ICU, and wherever else they were needed, 24/7 to hear their stories, normalize their emotions and share information and resources. Operation Uplift was so impactful that it was expanded to include patients and their families.

In a constant state of on-the-spot improvisation, the hospital placed beds “in places you would never imagine.”

– Jonelle Morris

“I know what a goldfish feels like”

Nearly a year after Hurtado sat riveted on his family’s couch learning about the Wuhan flight’s arrival at Riverside, he lay flat across it, coughing on Christmas December 2020.

Instead of watching the news, though, he looked at the readings on his hastily purchased oximeter and downed Pedialyte. Hurtado had been diagnosed with Covid-19 two days earlier and was trying to stay away from his wife and 21-year-old daughter who worked as a barista.

Although in good health with high energy levels, Hurtado had type 2 diabetes, which made him vulnerable to the worst of Covid-19. On December 26, his oxygen levels dropped and he gasped for air, comparing the experience to being a fish out of water. “I know what a goldfish feels like,” he said. As he contended with the highest fever of his life, his daughter drove him to the emergency room at RUHS Medical Center.

“Smell the roses, blow out the candles”

“The ER was packed. It was like an ant farm with people running all over the place,” said Hurtado.

He was isolated from other ER patients in a separate room at RUHS Medical Center as nurses darted in and out, placing him on supplemental oxygen. Hurtado was taken aback by “the bravery of them, their sense of duty.”

Later that night, a doctor visited, talking with him about the game plan. Hurtado’s stay would not be short; they wanted to keep a close watch. After being held for almost 24 hours in the ER area, Hurtado was brought upstairs in a gurney to the Covid-19 area as a scarce bed opened up.

After a few days, Hurtado suddenly deteriorated as he walked back from the restroom. “I wasn’t breathing out,” he said. Seconds later, “three or four people were right in front of me.” Respiratory therapists and nurses immediately replaced the small tubes going into his nostrils with a large oxygen mask. “They jacked it up from level four oxygen to the max, 15. And that scared me.”

Later that night, Hurtado heard the patient next door coughing. “He was fighting for his life too,” he said. He looked out the window and wondered: “Am I ever going to get out of here?”

Hurtado also worried for his wife and daughter, who had both tested positive for the virus shortly after his arrival at RUHS Medical Center. Luckily, they did not require hospitalization, but this would be the first New Year’s Eve in 30 years that he would not spend with his wife.

By morning, he heard the service trucks rolling in, a routine that reassured him, and the nurses in his room. They encouraged him to lay on his stomach and practice breathing “like you’re smelling roses and blowing out candles.” Determined to get better, he focused on this exercise constantly when he wasn’t sleeping.

“See, I told you the exercises work!” said one of the nurses who was happy to see Hurtado briefly stand in his room without his oxygen on January 3. Three days later, almost two weeks after he arrived at RUHS Medical Center, Hurtado’s wife picked him up and brought him home.

“Am I ever going to get out of here?”

– Jaime Hurtado

A lock of hair

But not everyone survived the second surge. “There was so much death around us,” said Morris.

For one family who had lost a loved one to Covid-19 and been unable to see her because of visitor restrictions, they wanted a final keepsake before her cremation: a lock of hair.

But they couldn’t afford the mortuary fee for the small cut. At a physician meeting, Morris and others discussed personally paying the amount to fulfill the family’s wishes when later that day, she and Dr. Shunling Tsang, who had cared for the deceased patient, walked down to RUHS Medical Center’s on-site morgue.

They went to relieve the nurses and staff who were moving bodies into three trucks recently acquired because the hospital had run out of space for the dead.

“Do you think we can find my patient?” asked Dr. Tsang. “Absolutely,” said Morris. They “led with their hearts,” she said, locating the deceased in one of the trucks, cutting the lock of hair and delivering it to the family.

“It was a tough thing to do,” said Morris about the stark and solemn moment. But she felt it was the right thing to do to bring some closure. “I would do it over and over again if it would provide peace of mind to the family.”

Vaccines on wheels

A ray of light for RUHS Medical Center, like for so many other overburdened hospitals around the country, was the vaccines.

For months prior to vaccine availability, Morris had been methodically planning the process for distribution that would focus on RUHS Medical Center patients and particularly vulnerable individuals to “really hit the diversity, equity and inclusion mark,” she said. To increase the hospital’s chances of doing so, she established entire teams whose sole, day-in-day-out focus was ensuring highly efficient distribution, especially for populations at highest risk and with the steepest infection rates.

Similar to the hospital’s approach to testing, RUHS Medical Center went to the community; they did not wait for vulnerable and busy populations to come to them. As of June 2021, RUHS Medical Center’s mobile team and pop-up clinics have put 2 million shots in arms, including at Martha’s Village and Kitchen, one of the largest providers of homeless services in Riverside.

And it’s wheels up again for RUHS Medical Center’s massive mobile health clinic, the same one that treated evacuees from Wuhan. This time, the clinic has been traveling throughout the Coachella Valley to ensure hard-to-reach residents have access to the vaccines.

“We’re really striving for the best.”

– Jonelle Morris

The babies are back

In February 2021, the babies returned to the hospital’s delivery units where earlier Covid-19 adults had gasped for breath and fought for their lives.

Down the hall, Morris affixed the hospital’s “I’ve been vaccinated” button on her lapel. She was “ecstatic,” as she described it, to have the vaccine out in the community and hopefully guarding against another devastating surge.

A few miles down the road, Hurtado was at home. He was looking at two photos on his phone that he snapped a few days after he left RUHS Medical Center. The first was from outside his hospital room. He took the photo from his truck in the RUHS Medical Center parking lot. He “stalked his room,” he said with a laugh, to remind him that he “got out of that one!”

Hurtado took another photo of a big banner sign outside the hospital that read, “Thank you RUHS Medical Center Heroes.” When asked why he took the photo, he replied, “To remind me of the people who cared for me and kept me alive.”

This blog is part of a series funded by the California Health Care Foundation.